FIELD NOTES BLOG

The Spring Invaders Among Us

As spring quickly approaches it brings with it beautiful rain storms, warm air breezes, and longer sunny days we will be shedding out thick winter coats and emerging from our dens to properly enjoy this fairer weather. Humans aren’t the only organisms that are taking advantage of the change in seasons. Springtime is a great time of growth in rebirth as plants begin to germinate and sprout out of the ground and animals return to the area to give birth. Thus turning the midwestern forests and prairies from drab, cold doldrums into verdant wonderlands ripe for endless outdoor adventures.

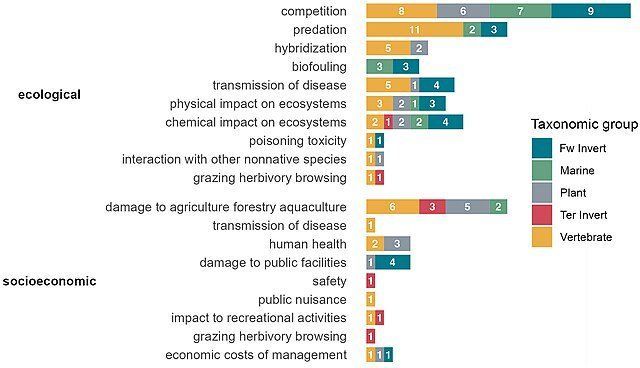

However, not all of this growth is desirable since Illinois is unfortunately home to several 100 species of exotic and invasive plants, animals, and fungi. We, humans, are to blame for this as our desire to spread across the planet and to experience things from around the world has resulted either directly or indirectly in the spread of a wide variety of species from their native homelands to new areas. Just the appearance of an ‘alien’ species in a habitat is not innate, it's when these species begin to spread and become successful; resulting in economic or ecological harm to the native species, crops, and livestock through competition, predation and in rare cases, hybridization.

In the media charismatic, invasive animals like feral hogs, pythons, and lionfish get all of the hype since they can be played up as ‘big bads’. But the most notable invasive species for the average nature enthusiast would be one of the dozens of plant species. They normally possess adaptations that make them highly competitive when compared to native plants, most notably the ability to quickly germinate, leading to them being some of, if not the first plants to emerge from the barren ground. This means that they have first dibs on all of the nutrients and water in the soil starving out native plants, preventing their growth. Even if a native can sprout amongst them they will have a hard time photosynthesizing as the earlier invasives would have already fully unfurled their leaves, leaving natives struggling in the shade. So as we begin our journeys back into the woods and water of Winnebago County we must keep our eyes peeled for our most common culprits.

The first and most abundant of these plants would have to be garlic mustard (Alliaria petiolata) , a native of Europe and Asia which was introduced to North America in the mid-1800s. As soon as the snow melts and the sun peeks through the overcast winter and early spring skies garlic mustard begins to emerge and take over the forest floor. At this time of year if you are seeing green amongst the roots of trees it's these that you see, dominating the understory and reducing biodiversity. They can be identified by a circular arrangement of heart-shaped leaves with heavily toothed margins. In their second year they begin producing small, white cross-shaped flowers. It can also be identified by its namesake smell, for when you pick a leaf of the plants and crush it between your fingers it will give off a garlicky odor. Even though the plant is invasive it does have its uses, most notably the fact that it's edible. You can harvest the plants at any stage and eat them but it's best to harvest younger plants since they are tastier and require less thorough cooking as they contain far less cyanide than the older plants.

Another plant of note would be the orange daylily (Hemerocallis fulva) also known as the ditch lily. This plant is master of growing in poor habitats such as roadsides, cemeteries, railroads, and suburban green spaces. They can be identified by their 3-6’ tall stalks and their rosette of sword-shaped leaves located at the plant’s base. The leaves of this plant have a protective waxy coating which eleades it to being less affected by water loss and herbicide treatments. Even though their Orange flowers appear for only a single day in summer, the herbaceous body of the plant emerges early in the spring in huge clusters in order to drown out native plants and hog all of the sunlight, water, and nutrients. The plant is a persistent problem as they are a long-lived perennial that will renege in a location for years and years. However just like with garlic mustard this plant is edible, all parts of the younger plants are non-toxic and edible to humans.

Siberian squill (Scilla siberica) is a special case amongst the spring plants as this is the only time you'll see them above ground. This is because it's a spring ephemeral, meaning that the plant germinates, emerges, blooms, and enters dormancy all before spring is even over. Their cold-tolerance allows them to emerge right after the snow melts and gives them the ability to utilize resources because any other plant is able to compete with them. Early emergence aids in reproduction as well as seeds can enter the soil before those of other plants and also miss all of the seed predators that are still away or dormant due to cold. It is easily identifiable by its 5 inch grass like leaves, and bell shaped blue flowers which form in groups of 2-3 at the top of the stem. Its beauty has long made it a favorite among gardeners contributing to its spread.

The last plant I'm going to cover is going to be another old world invader, the wild parsnip (Pastinaca sativa). This is the wild ancestor of the parsnips that are seen commonly in kitchens and restaurants. Their flowers are formed in loose groups at the top of the stem; they are yellow in color and possess 5 small petals that curl inwards. The pinnate oval-shaped leaves of the plant are compound, hairy, broad, and toothed. Stems are 4-5 tall. The seedlings of the plants emerge between February and April soon after the snow melts. The seedlings are similar to the adults but smaller, less hairy, and having no flowers. Dominante in areas of rich, alkaline, moist soils; especially thriving in disturbed habitats such as abandoned pastures, croplands, and roadsides in which native plants have been removed or have yet to become fully established. Even though its cultivated cousin is a popular food crop this variety serves as a serious threat to human health and safety. Though the roots of the plant are actively nutritious for humans the leaves and stem possess a sap that is toxic though both eating them and skin contact, with the sap causing burning blisters to skin when it is exposed to UV rays from the sun.

Now that we've covered a few of the floral species of notes it's time to move on to a more mobile and active enemy of our natural spaces; the fauna. Invasive animals in Illinois are far more ‘naturalized’ and easy to pass over as they are either ubiquitous with living in the state or are very similar to native species. The species of note is a common visitor to bird feeders and urban green spaces, the European House Sparrow (Passer domesticus). This bird was introduced in the mid-1800s as a few Shakespeare fans in NYC wanted to experience their favorite writer’s birds firsthand. Even though they live in the area year-round, thanks to the abundance of food provided by feed and leftover corn in fields, they become more active in the spring as they begin to nest. This is of importance as they are cavity nesters who enjoy making their nests with human structures, increasing our interactions with them. They are aggressive competitors to native bird species like eastern bluebirds, purple martins, and tree swallows, being known to attack them and drive them off nest sites.

A species you’ll run into while on the water we have the rusty crayfish (Faxonius rusticus). Which is a vagrant that has migrated from our easterly neighbors of Ohio, Indiana, and Kentucky. Color ranges from greenish-gray to reddish brown but all individuals have two large rusty spots on the sides of their backs. Maxing out at 1.7 inches in length they are much larger than our native species. Couple this with their aggressiveness and you have a recipe for ecological disaster. Rusties have taken over most of the waterways in Illinois, displacing our native species and making it the dominant resident. Even Severson isn’t immune from their effects and you can see them in our creek as they begin to emerge from their burrows.

We need to keep in mind that our ecosystems, for as long as they've been around, are still fragile buildings whose architecture is dependent on the millennia-old interactions between species that have evolved together. So by disturbing this balance through continuing the tolerance and propagation of invasive species, we can bring the whole thing crashing down. For the sake of our posterity we should, no, we must do better about educating ourselves on the invaders that lurk among us.

RECENT ARTICLES