FIELD NOTES BLOG

Glacial History of Northern Illinois

Illinois is the second flattest state in the nation! Have you ever wondered why? The answer has a lot to do with mammoths, growing corn, and far-away rocks. Glaciation has had a significant impact on forming the topography in the Midwest United States, specifically in Illinois. Illinois was a moving ground for glaciers, carving the land underneath it, making it super flat. The answer has a lot to do with mammoths, growing corn, and far-away rocks. Before the ice age there were no

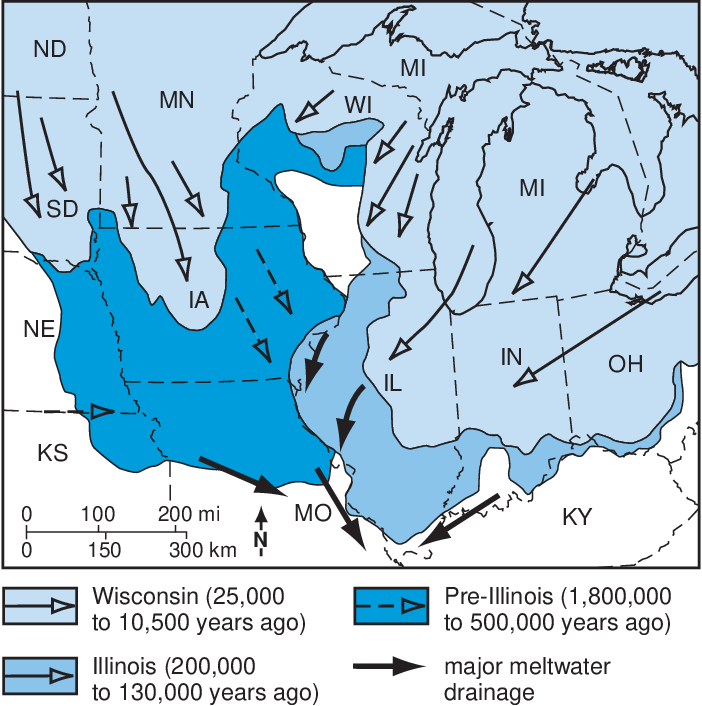

Great Lakes, only shallow basins, except for Lake Superior, which had formed earlier as a result of the midcontinent rift system. Glaciers that originated in Eastern and Central Canada extended into parts of Illinois during long cold periods, where they reshaped the land. There are three glacial periods which have affected Illinois, known as the Pre-Illinoian, Illinoian, and Wisconsinian, and they invaded Illinois during the Ice Age, which extended from 2.4 million years to 10,000 years ago. During this time, glaciers were invading Northern Illinois repeatedly, forming the modern landscape we know and see today.

Pre-Illinoian

The Pre-Illinoian was a glacial period ranging from 1.8 million - 500,000 years. During this time, glaciers were advancing from the West, and the glaciers moved the land they overrode, leveling and filling many valleys. There were a lot of alternating stable and unstable intervals where these glaciers would go through a period of advance, then they’d retreat, and then they would advance again; but this occurred spontaneously and was inconsistent with its duration. While this was the first major glacial period to come through Illinois, not much evidence

remains of it. Pre-Illinoian deposits are irregularly distributed in Illinois, and where present, they are usually overlain by younger drift. Most of the land that was carved out by the Pre-Illinoian has been buried, eroded, or removed by younger glaciations. In addition, the Pre-Illinoian glaciation is responsible for reducing a large portion of the relief of Illinois’ topography.

Illinoian

Then came the Illinoian, which was a glacial period ranging from 200,000 - 130,000 years. This glacial period was very extensive, and at one point, nearly

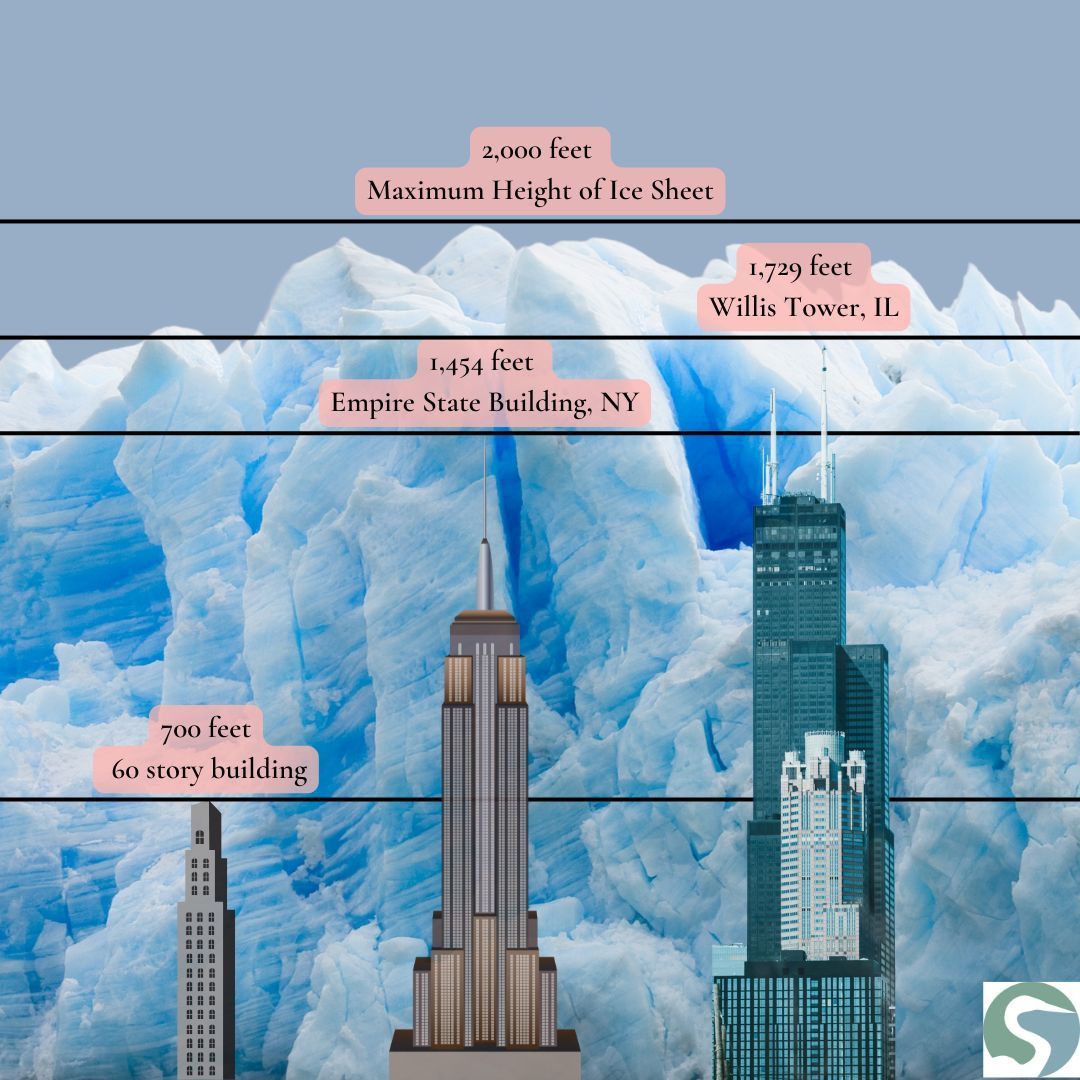

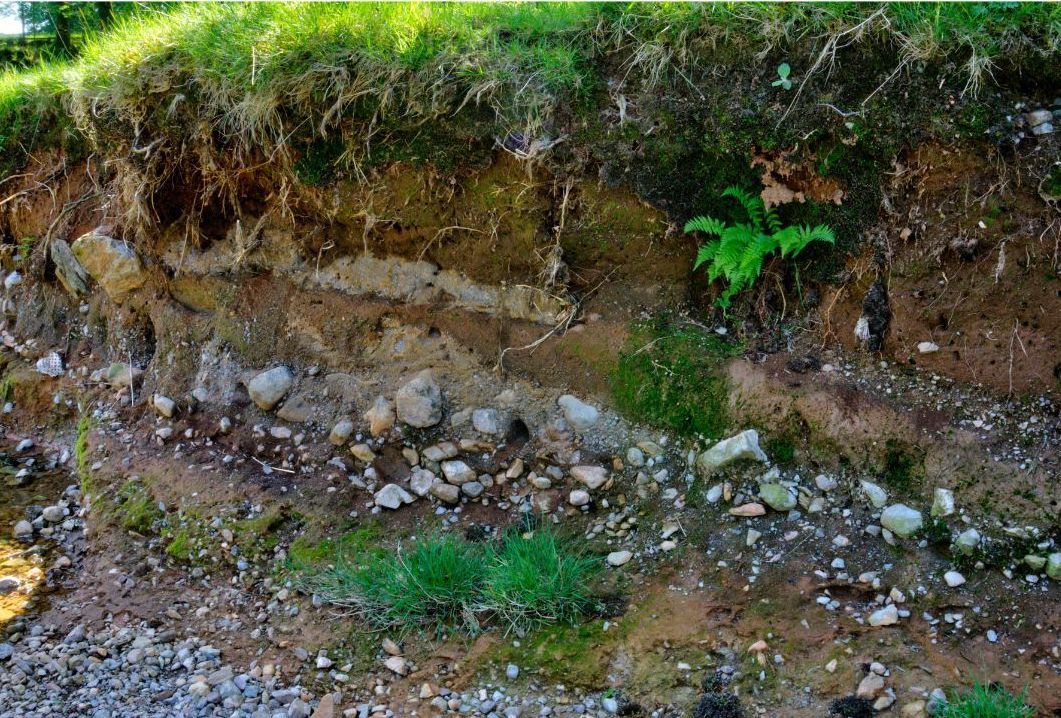

85% of the state was covered with ice! Glacial ice from this period reached as far south as Carbondale, Illinois, which is the most southern point that glaciers have ever reached in the northern hemisphere. During the Illinoian, some sections of the glaciers in Northern Illinois were about 2,000 feet thick, while other areas of the state were covered by ice masses about 700 feet thick, as tall as a 60-story building! The Illinoian glacial advances left behind some low-relief, rolling ground-moraines (an uneven sheet of glacial debris deposited underneath a glacier, creating a relatively flat layer of sediment across a wide area). This glacial period caused many of the preglacial bedrock valleys throughout the state to be partially filled with thick deposits of outwash sand and gravel, most prominent along Northern and some of Central Illinois. While some of the evidence of this glacial period has been eroded, buried, or removed, portions of glacial till and erratics (glacially deposited rock) still remain, as they weren’t reached by the younger glaciations.

Wisconsinian

Lastly, came the Wisconsinian, which was a glacial period ranging from 30,000 - 10,500 years. During this time, glaciers were advancing from the Northwest and the Northeast and covered much of the Northern and East-Central parts of our state. The Wisconsinian till is the least compact of the till from the three glacial periods, due to it being the last major glaciation to occur in Illinois. This means that there is also the most remaining evidence left over from this period, with many moraines and kettle lakes, such as Lake Michigan in Northeastern Illinois, they’re all remnants of this glacial period and show what got carved out during the Wisconsinian period. About

11,000 years ago the climate warmed, and the glaciers began to melt and retreat Northward from the Lake Michigan Basin for the last time, resulting in a lower water level, and the formation of large lakes all over the land that the glacier had previously occupied. Then for about 5,000 years, as the glacier retreated Northward across Canada, the Upper Great Lakes drained to the Northeast across land that was still being squished down due to the weight of the ice sheet, and channeled into the Atlantic Ocean. Then, roughly 6,000 years ago, the Upper Great Lakes Basin started to fill, and pushed lots of water out of its distributary outlets. This drainage was short-lived, however, because about 4,000 years ago, the drainage from the Lake Michigan Basin was captured by an outlet at Port Huron in Michigan, and then the modern Great Lakes drainage system formed. The deposits left behind from the Wisconsinian period are what contribute to the uppermost earth materials throughout most of Illinois, they cover over 90% of the state!

During the Pleistocene Epoch (2.6 million-11,000 years ago) about

85% of Illinois was covered by glaciers. When the glaciers advanced into Northern Illinois the weather was very different than it is today. The average yearly temperature was slightly above freezing, and most of this area's precipitation was in snow form. Northern Illinois was a tundra that many large extinct mammals inhabited! A few of the mammals that lived here included the mammoth, American mastodon, Jefferson ground sloth, giant beaver, saber-toothed cat, snowshoe hare, and the arctic shrew. The black bear, gray wolf and wapiti lived in Northern Illinois during the Ice Age and were still inhabiting here up until the 1860’s due to habitat loss and unregulated hunting. Eastern cottontails, deer mice, gray squirrels, white-tailed deer and raccoons are a few of the only mammals that were alive during both the Ice Age and the present day in Illinois! Fossils of these animals have been found all along Northern Illinois, with some of them even extending into Central Illinois. However, as the climate warmed and human activity altered the landscape, many of the mammal species that roamed Illinois were short-lived. Once humans settled in Illinois, they began changing the land from its natural prairie, woodland, and wetland, with the intent to farm. However, these decisions affected the native mammals, causing them to either become extinct, or migrate to different areas. There were many mammals which weren’t able to survive the warming temperatures, leaving behind a vastly different ecosystem from the one that existed during the Ice Age.

Although Illinois has endured lots of glacial activity, there are parts of the state that were untouched by them! The

driftless area is often used to describe the area of Southwestern Wisconsin and Northwestern Illinois that was untouched by glaciers. Scientists had noticed that these areas were lacking glacial sediment, indicating that this portion hadn’t been covered by glacial ice, and that the land appeared different in topography from the rest of Wisconsin and Illinois. Scientists began to study these small areas, the Northwestern corner (the Galena area), the extreme south (the Shawnee Hills) and a small area in Western Illinois, and the similarities between them. When comparing these regions to each other, they realized that the cliffs and rocky ridges of these areas were heavily exaggerated in relief. This means that these areas were never covered by glaciers, but instead, they have primarily formed as a result of rivers cutting down into the surrounding bedrock.

Pleistocene glaciers and the waters melting from them forever changed the landscapes that they covered. In most of Illinois, glacial deposits buried the old hill-and-valley terrain and created the flatter land forms, which eventually became the prairies of Illinois. Most of the landscape has been developed on earth materials deposited by glaciers of the Pleistocene Ice Age, as well as from wind, and streams. Where the thickest drift occurred in major pre-glacial river valleys: cutting into bedrock, changing the course of rivers, and creating new landforms on the surface, forever changing the land we know today as Northern Illinois! The impact of glaciation, combined with the changes brought by climate shifts and human activity, has created a unique environment in Illinois that is rich in both natural history and geologic evidence. Understanding the state's glacial past not only reveals its physical history but also provides insight into the ecosystems and animal life that once thrived here, illustrating the ever-changing relationship between the land and its inhabitants.

Sources:

Killey, Myrna M. “Illinois’ Ice Age Legacy .” Semantic Scholar, Champaign, IL : Illinois State Geological Survey, archive.org/details/illinoisiceagele14kill. -picture

“Before the Ice Age.” Lost Rivers, The Toronto Green Community, www.lostrivers.ca/content/points/beforeice.html#:~:text=Before%20the%20Ice%20Age%20there,Central%20North%20American%20Rift%20System.

Abert, Curtis. Modeling Glaciated Terrains, Illinois State Geological Survey, proceedings.esri.com/library/userconf/proc96/TO100/PAP061/P61.HTM.

Piskin, Kemal, and Robert Bergstrom. “Glacial Drift in Illinois: Thickness and Character.” State of Illinois Department of Registration and Education, Illinois State Geological Survey, library.isgs.illinois.edu/Pubs/pdfs/circulars/c490.pdf.

Association, Canal Corridor. “Ice Age Geology.” Canal National Heritage Area, Stories of the I & M Canal National Heritage Area, iandmcanal.substack.com/p/ice-age-geology.

“Geology of Illinois.” Department of Natural Resources , Illinois State Geological Survey, dnr.illinois.gov/content/dam/soi/en/web/dnr/education/documents/onlineintroillinoisnatres-5-6-.pdf.

Carson, Eric C, et al. The Driftless Area - WGNHS, Wisconsin Geological and Natural History Survey, wgnhs.wisc.edu/pubshare/ES057.pdf.

RECENT ARTICLES

Our Mission: To link people to nature through education and research, in the northern Illinois and southern Wisconsin area. We promote awareness of the natural world, fostering respect, enjoyment, and preservation now and in the future.

Contact us

8786 Montague Rd.

Rockford, IL 61102

Business Hours

- Mon - Sat

- -

- Sunday

- Closed

The Grove Nature Playscape and the trails

are open from sunrise to sunset.

Website Navigation

Business Sponsors

Slide title

Write your caption hereButton

Slide title

Write your caption hereButton

Slide title

Write your caption hereButton

Slide title

Write your caption hereButton

Slide title

Write your caption hereButton

Slide title

Write your caption hereButton

Slide title

Write your caption hereButton

Slide title

Write your caption hereButton

Slide title

Write your caption hereButton

Slide title

Write your caption hereButton

Slide title

Write your caption hereButton

Slide title

Write your caption hereButton

Slide title

Write your caption hereButton

Slide title

Write your caption hereButton

Slide title

Write your caption hereButton

Slide title

Write your caption hereButton

Slide title

Write your caption hereButton

Slide title

Write your caption hereButton

Slide title

Write your caption hereButton

Slide title

Write your caption hereButton

Slide title

Write your caption hereButton

Slide title

Write your caption hereButton

Slide title

Write your caption hereButton

Slide title

Write your caption hereButton

Slide title

Write your caption hereButton

Slide title

Write your caption hereButton

Slide title

Write your caption hereButton

©2023 | All Rights Reserved | Severson Dells Nature Center

Website powered by Neon One