FIELD NOTES BLOG

Chytrid Fungus and Frogs

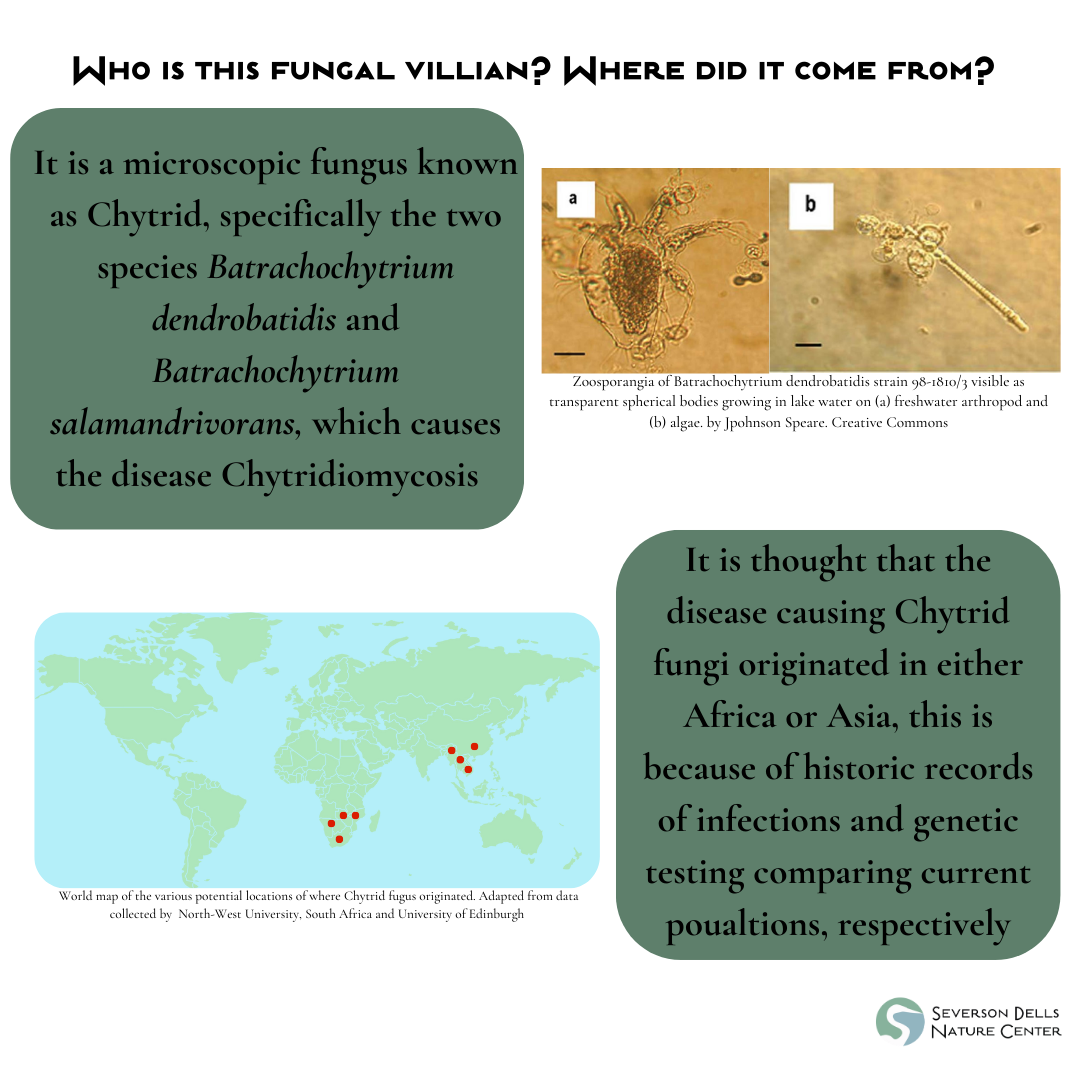

Our amphibians- frogs, toads, newts, and salamanders-are under threat. This probably isn't news for many of you, as ecological news outlets have been raising the alarm about how many species have been disappearing from our waterways and wetlands. However, you may not know which enemies we are facing. In many cases it's regular, repeat offenders associated with human interactions in the environment; things such as water pollution and habitat loss. Even though these are quite devastating, there is another, one that is far more sinister, going undetected by the general population and has non known solution for its destruction. This villain would be none other than a microscopic organism called the chytrid fungus, or as it is known in the scientific community, Batrachochytrium dendrobatidis and Batrachochytrium salamandrivorans.

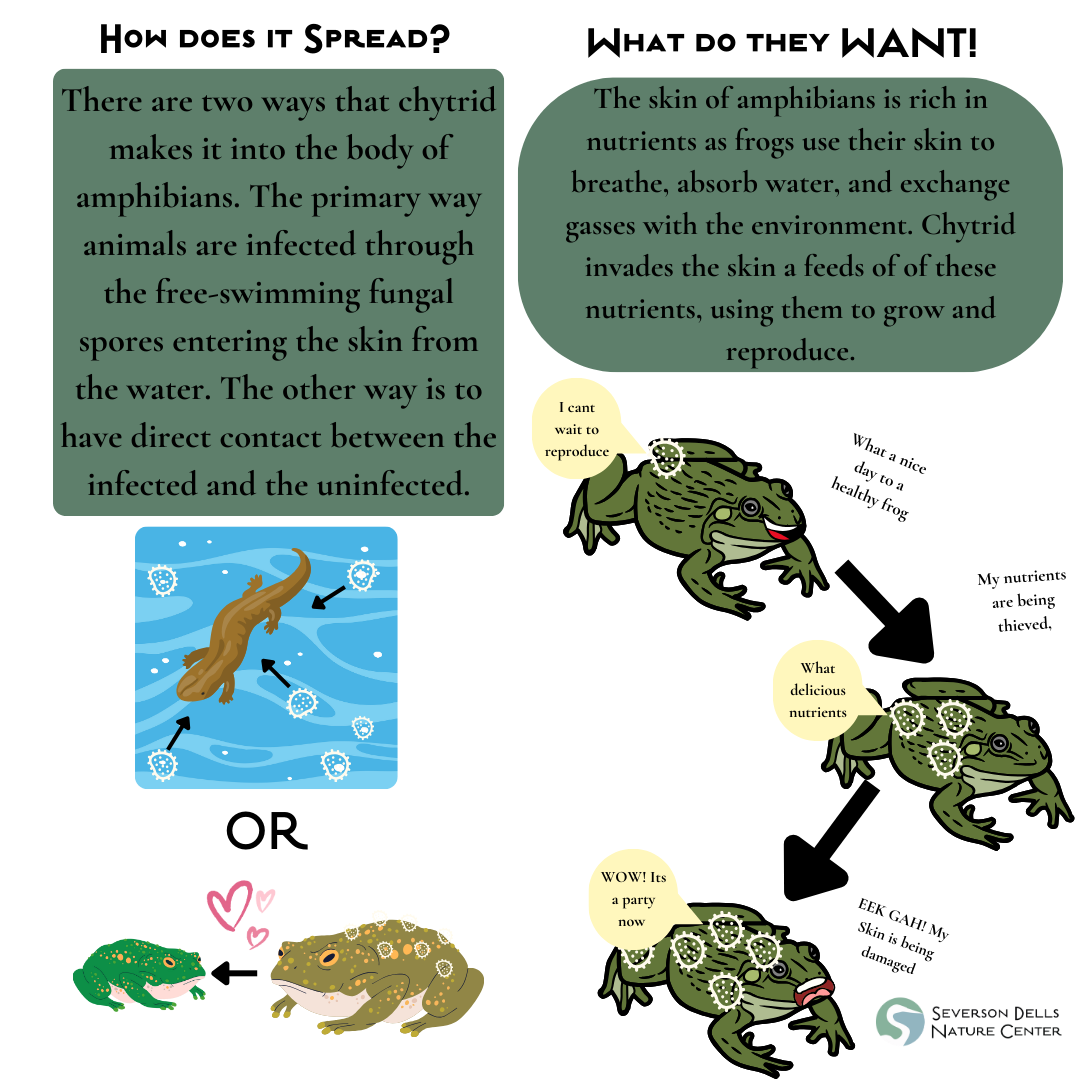

There are over 1,000 different species of chytrid fungus found around the world and not all of them are not problematic (1). Most live their lives as simple, microscopic fungus, who are perfectly content with freely living in soil and water where they break down decaying plant matter. The two species that I mentioned earlier, B. dendrobatidis and B. salamandrivorans, are very different from the others as they are parasitic. This means that they survive by living in or on another organism, known as a host, and taking nutrients from them which results in bodily harm or occasionally death. Chytrid fungus lives on and inside the skin of amphibians and feeds off of the nutrients that are in the blood vessels in the skin. This results in a disease called chytridiomycosis (6). The fungus can spread in two ways; the first is direct contact between an infected animal and an uninfected one as this allows the fungus to jump to a new host. The second is for the amphibian to come in contact with infected water as the babies of the fungi are free-swimming and will infect any suitable host they come across.

Chytrid fungus steal nutrients in amphibian skin and makes it more difficult for them to breathe through their skin. As the fungi feeds it begins to grow and spread inside the skin of the frog which eventually gums up the pores in the skin, thickening it and making it so that the skin is unable to do its job as a breathing organ. This would be akin to having our nose and lungs filled with mushrooms that prevent us from being able to breathe. The continued growth of the fungi in the skin further saps away nutrients from the animal resulting in severe emaciation, also known as weight loss. As the disease progresses the skin begins to change from the natural color to a sickly gray-white coloration and begins to have open sores form on it. Besides the physical attributes of the disease, it also puts a lot of mental strain on the animals, leading them to be sluggish and lethargic As both symptoms progress it eventually leads to the skin completely shedding away. Unfortunately the sum of these symptoms result in death in up to 100% of infected individuals depending on location and species (1).

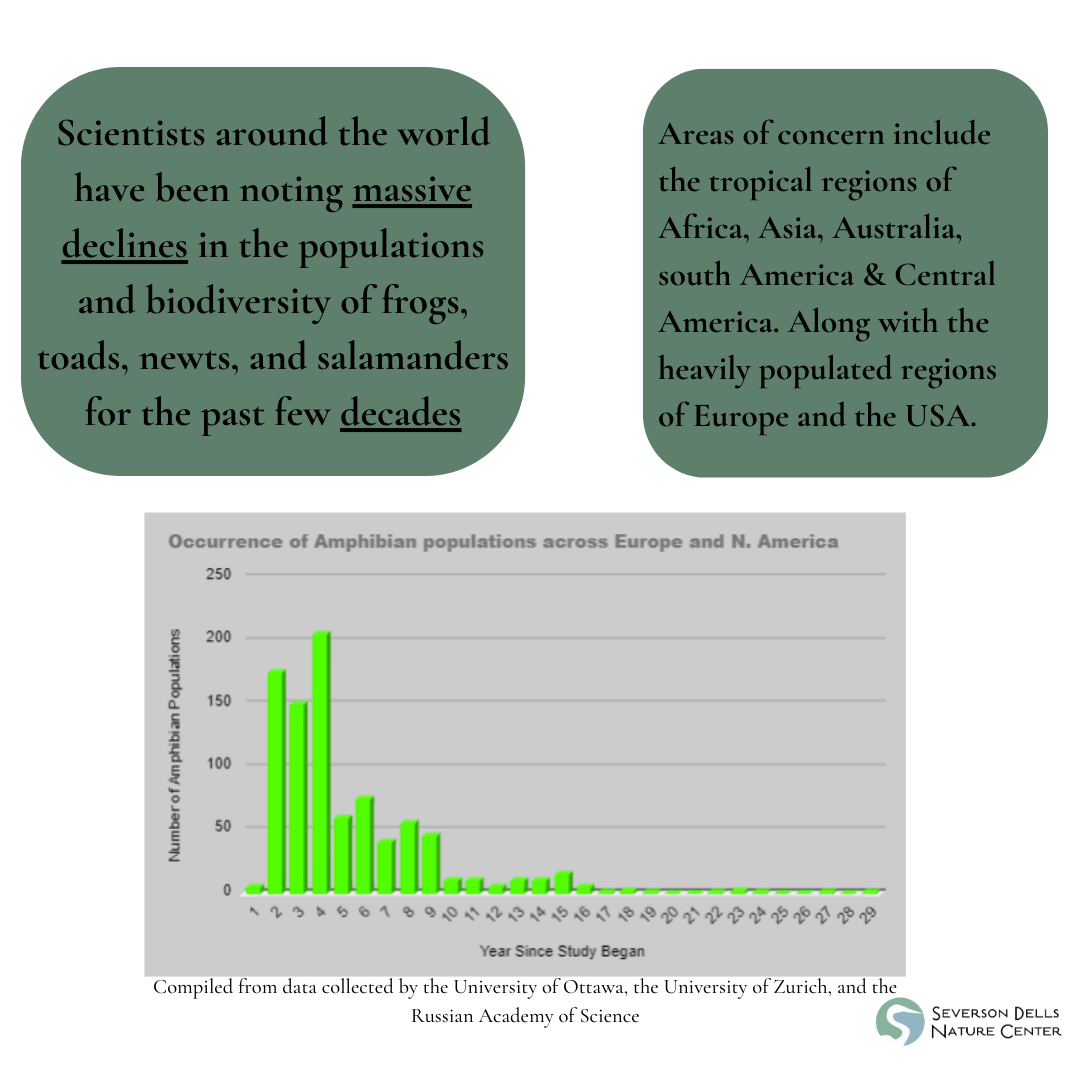

This disease wasn't properly discovered until 1993 after a scientist was studying why there were huge declines in frog populations in Australia (2). After this information was made available to the greater scientific world, researchers in other places began to look at their own populations of frogs and salamanders to check for it. This is when they realized that it had already spread across the world, being present on every continent. Leading to the ascension of the fungus to being one of the leading reasons for amphibian population declines across the board (3). However, this illness is not an entirely new thing, as the oldest documented occurrence is from 1863 which showed a frog from South America being infected (6). Due to how widespread it is, it has been hard for scientists to determine where exactly it originated. The best hypothesis is from Southeast Asia or Southern Africa with it being spread through the trade of frogs in the 20th century for research, food, and pets (5).

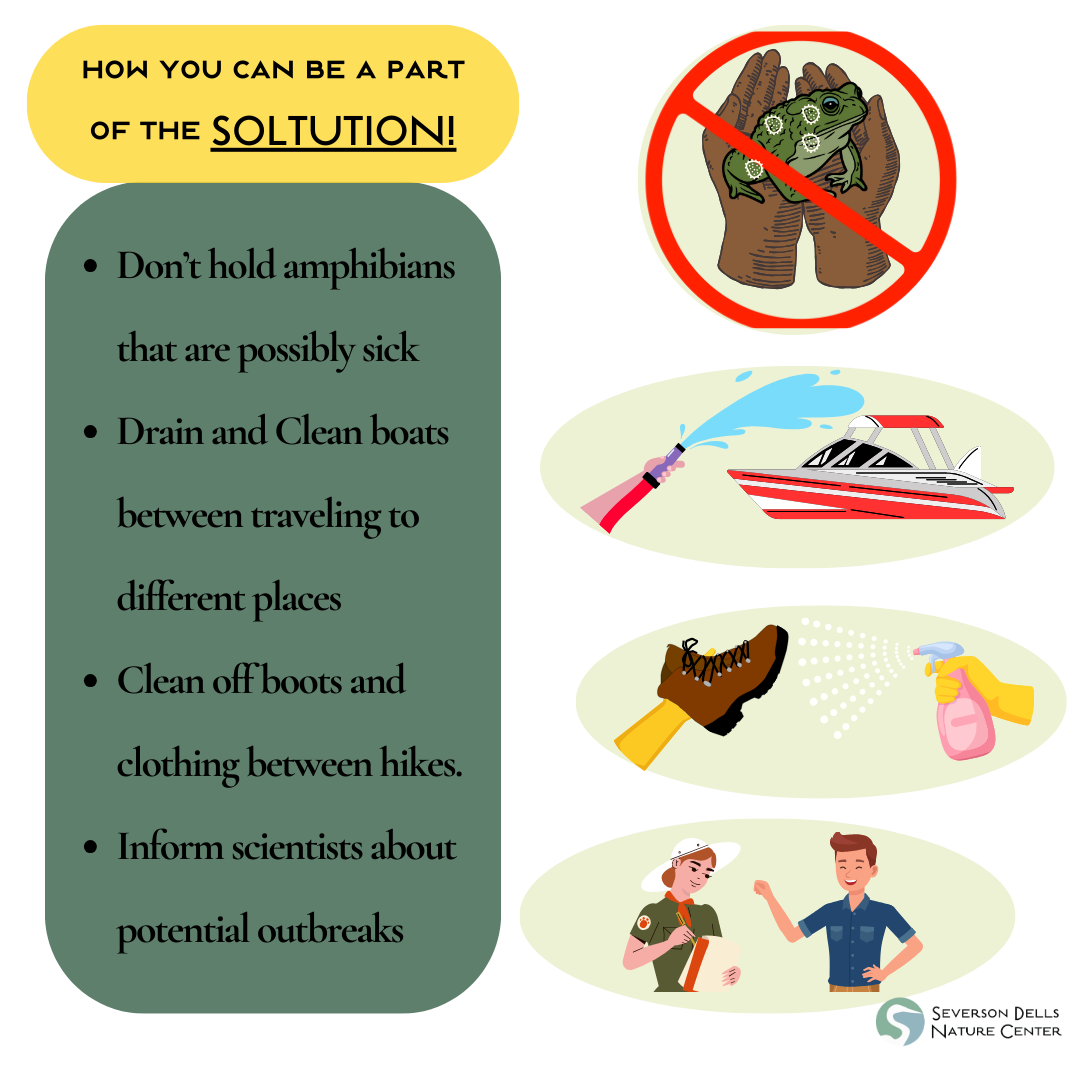

All is not lost however. Research is well underway in many places around the world to understand how to treat the disease. The two most well-studied and viable treatments are through the use of antifungal medications and heat therapy (4). You might be asking, “what can I do to help?”, and there are some good ways for you to be a part of the solution. The best and most simple way is to limit your direct interactions with frogs and other amphibians. You should only touch them when necessary; like if you have to remove them from a dangerous or undesirable location, and when interacting with them make sure to wear disposable gloves. This might seem like a given but when interacting with amphibians do not move them from one area to another since that frog might be unknowingly infected and spread the fungus to a new population. Mud and water that are left on aquatic recreation equipment such as boots, boats, tires, and fishing gear all have the potential to carry the disease fungus from place to place. So it's important to clean and disinfect all of your equipment before moving between different bodies of water. You can use anything from vinegar and soapy water to harsher chemicals like lysol or bleach to kill the fungi. You can even get involved though the scientific research aspect of combating the scourge since many environmental agencies, such as the US Fish and Wildlife Service, often run programs where they give out resources for everyday people to collect skin samples from local frogs to be used for detection and monitoring. Even if your local groups aren't doing a project like that you should always report mass death events or suspicious frogs to the department of natural resources Hopefully with a better understanding and more publicity this particular strife can be ended.

- Amphibian Ark. (2022a, May 16). Chytrid fungus. Amphibian Ark. https://www.amphibianark.org/the-crisis/chytrid-fungus/#:~:text=salamandrivorans%2C%20commonly%20known%20as%20%E2%80%9Camphibian,as%20decomposers%20of%20plant%20material.

- Australian Government: Department of Sustainability, Environment, Water, Population and Communities. (2013). Chytridiomycosis (Amphibian chytrid fungus disease). Department of Sustainability, Environment, Water, Population and Communities.

- Collins JP. Amphibian decline and extinction: what we know and what we need to learn. Dis Aquat Organ. 2010 Nov;92(2-3):93-9. doi: 10.3354/dao02307. PMID: 21268970.

- Parker JM, Mikaelian I, Hahn N, Diggs HE (2002). "Clinical diagnosis and treatment of epidermal chytridiomycosis in African clawed frogs (Xenopus tropicalis)". Comp. Med. 52 (3): 265–8. PMID 12102573

- Weldon; du Preez; Hyatt; Muller; and Speare (2004). Origin of the Amphibian Chytrid Fungus. Emerging Infectious Diseases 10(12).

- Whittaker, Kellie; Vredenburg, Vance. "An Overview of Chytridiomycosis". Amphibiaweb. Retrieved 29 September 2016.

RECENT ARTICLES